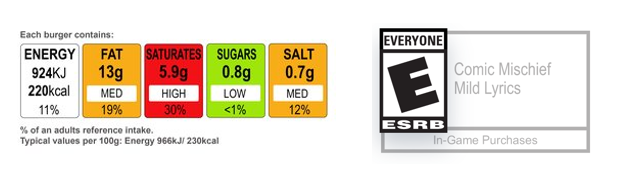

I’ve been having a think recently about the kinds of consumer protections and indicators people get when they’re buying stuff. With food, the EU has strict safety laws and you get nutritional indicators like the UK’s traffic lighting labels. With video games there is less legislation (for now), but you still get content labelling done by the ESRB. This legislation and manner of labelling can never be perfect, but it is still incredibly useful when shopping around.

With the advent of “smart” technology well in progress, I think the time has come for adapting legislation and applying such labelling to technology in all its forms.

The current state of affairs

Smart technology has the potential to change our lives for the better, but poor quality “smart” tech can make life a lot more difficult. This comes as a result of a number of problems:

- Support being too costly – this biggest “smart” security risk facing consumers right now is probably smartphones losing security support

- Deliberate action – where companies want you to buy the newer models of their “smart” device, so stop supporting older ones

- Greed – tracking you and putting ads on your “smart” devices because the thousands you spent on the device were not enough

- Incompetence – companies simply not bothering with security at all

The UK’s DCMS has recently been whispering of ensuring that, at the very least, “smart” devices sold will have decent security, suggesting:

- Unique default passwords

- Accessible customer support and easy vulnerability reporting

- Disclosure of how long security updates are offered

But as reported by Which, this is just a proposal, and I can’t find an actual government source on that right now, so it could be a while before this is actually enforced in any way.

Below is my take on what “Smart” Tech legislation could look like, and suggestions for helpful labelling that would empower consumers to make sensible choices.

Proposed Legal Requirements

Anything that has the potential to talk to the internet, either directly or through some kind of proxy (such as a “Smart” home hub) must be protected. The proposals mentioned earlier are a must for decent security, but I would go further. Decent security requirements that come to mind, which ought to be guaranteed by legislation, include:

- Unique passwords per-device – Make these long and complex. Chances are the device will be set up and controlled by an app, so you shouldn’t need to enter it more than once.

- Separate passwords for root access – If a device has some form of “root” or “admin” access, have this use a different account and password to the usual access password

- Mandatory encryption for all communications – HTTPS is free. No device should be communicating anything insecurely.

- No internet if it’s not necessary – GDPR makes it illegal to ask for data that isn’t necessary for a service to function. Enact the same logic to “smart” devices. If it can function fully by intranet, bluetooth or some other limited connection – use that instead. Any internet access ought to be fully justified*.

- Whitelist who the device responds to – If Internet access is required, devices must have a firewall in place to only respond to communication from authorised sources.

- Security Updates guaranteed – I would suggest 3 years as a minimum during which security updates are guaranteed to be delivered. Make update packages easily accessible online and over the air for at least the security update period + 1 year

- Easy Reporting – An easy contact location for reporting vulnerabilities – either digital or physical

- Transparency – In the event of a security failure, the company must publicly disclose what the failure was, who (if they know) was affected, how many devices were affected, and how to secure devices

- Sustainability – Devices should be constructed in a way that makes them easy to repair and recycle

- Consumer protection – For those users who want to tinker with their devices for their personal use, they should be given legal protections to do so. Whether this is bypassing DRM, installing their own security updates, adapting 3rd party components for personal use.

Proposed Labelling

In addition to the baseline legal requirements, companies selling “smart” tech must disclose exactly how it will operate to consumers ahead of purchase. This is where I would suggest some kind of standardised labelling scheme that describes the Normal Operation† of the device.

Categories I think that are worth including are:

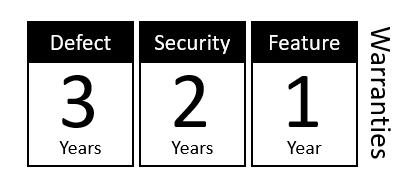

Warranty Period

State up-front how long a 3-component warranty will last. Currently companies and sellers offer a hardware defect warranty – If a device breaks down within a set amount of time, it is covered to be refunded, repaired or replaced. I would suggest expanding this to:

- Defects in either the software or hardware which are not the fault of the customer

- Security updates which are guaranteed within the specified number of years

- Feature updates which come with a road map describing what & when new feature will be delivered, if they were advertised

A hardware defect warranty may be covered by the seller of the device, not the manufacturer. But everything else would need to be treated as a manufacturers warranty.

If a manufacturer should fail to meet the expectations they set at time of sale, then they would be liable to compensate the customer who bought the goods. The labelling will make it explicit how long these periods will last

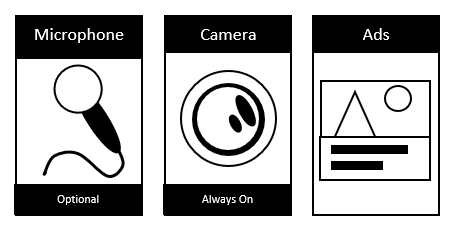

Privacy

With technology, privacy is an increasing concern. I would propose that if a device could in some way impact privacy during normal operation, it should be disclosed properly. It might seem obvious that some features like a microphone are present, but this is not always the case.

- Sensors such as Microphones, Camera, ECGs, anything which may track personal data should be disclosed

- It should be stated if sensors can be disabled or if they are always on during normal operation of the device

- If the device will serve advertisements, product placement or sponsored content during normal operation of the device, this must be stated

An additional privacy concern is that of external services. Such as requiring a connection to Google or Amazon. This is usually to be disclosed up-front, and I don’t see legislation being required for this. Google Assistant and Amazon Alexa usually take this as a form of advertising. But in case these connections should start being hidden in small print, mandatory 3rd party connections should be disclosed prominently as well as if they can be disabled.

In the event that an optional sensor or service is disabled, an explanation of how this affects device functionality must be given, though this need not be on a label.

If the device being sold itself was purely a sensor, and not a smart device in its own right, it wouldn’t need to include a label. I would hate for this to devolve like the cookie warning situation.

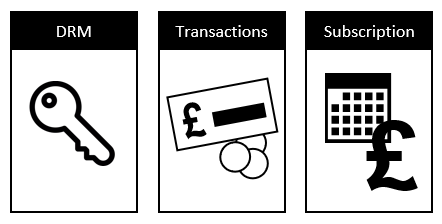

Limiters

Many technologies these days come with some form of limiter‡ which prevents the device from being used in certain ways, or requires financial transactions to fully function. These ought to be disclosed up front.

- DRM comes in many forms – One that I am most displeased with is the tech industry learning the wrong lessons from printers and putting everything in pods which are guaranteed to only work with specific devices and not “support” 3rd party alternatives. Any kind of DRM that limits use of the device should be disclosed up front.

- Transactions that gate off part of a devices functionality until an extra payment is made must be disclosed

- Subscriptions – If a device’s functionality relies on a server’s continued support, it is natural for a company to want to charge a subscription. Details of this must be cleanly disclosed up-front, including how functional the device will be if the subscription expires.

These limiters will likely require more detailed explanations that cannot be simply put across in an icon on a box or display unit. But the presence of the label will give consumers the choice of investigating further. Previously, this may not have been possible due to information being hidden in legalese texts.

After Sale Changes

A nice side effect of requiring labels at point of sale is it requires companies to disclose plans for their devices up front. If a company wanted to change tactic, such as introducing a subscription 6 months after sale, then they should be held in breach of the law for not disclosing this up front.

The labelling and descriptions given at point of sale should be upheld as a contract.

Final Thoughts

Government intervening with businesses is always a messy subject, but as I see what tech companies big and small get up to, I am increasingly in favour of it. Especially when the main aims are to empower consumers.

I doubt this will go anywhere soon, but it would be nice to see it happen before everything becomes “smart”.

Leave a comment if this sparks some thoughts!

Some iconography taken with permission from Microsoft or Freepik @ Flaticon

* No Internet

Is a “smart” device that doesn’t connect still “smart” in the traditional sense? Maybe not, but the device designers who are willing to make that choice are smart.

† What do I mean by “Normal Operation”?

Example 1: Smartphone and adverts. In normal operation, a bare bones smartphone will not serve adverts, so a label would not be needed. But if a phone came with pre-installed apps that did serve adverts, then a label would be required.

Example 2: External microphone. If a device did not come with a microphone, but one could be added through a 3rd party component/service installed by a user, then a label would not be required as adding this component is not “normal operation”.

‡ Limiters

Come to think of it, warnings about limiters could just as easily be applied to a lot of software, let alone hardware in recent times.